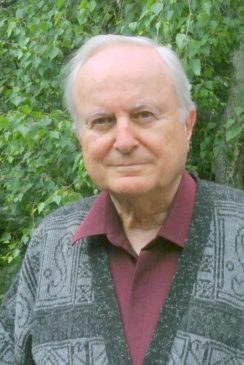

Alexander Shurbanov (Sofia, 1941) has published twelve volumes of poetry and six collections of essays. Shurbanov is the Bulgarian translator of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Milton’s Paradise Lost and Samson Agonistes, Coleridge’s poetry and prose, Dylan Thomas’s poems, Beatrix Potter’s tales, a collection of nursery rhymes, etc., as well as of Shakespeare’s mature tragedies. He has also translated a representative collection of Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry. For over four decades Shurbanov has taught English literature at Sofia University and has published a number of literary critical books dealing with the English Renaissance both at home and abroad. He is the winner of a number of prestigious awards as a writer, translator and scholar.

Alexander Shurbanov (Sofia, 1941) has published twelve volumes of poetry and six collections of essays. Shurbanov is the Bulgarian translator of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Milton’s Paradise Lost and Samson Agonistes, Coleridge’s poetry and prose, Dylan Thomas’s poems, Beatrix Potter’s tales, a collection of nursery rhymes, etc., as well as of Shakespeare’s mature tragedies. He has also translated a representative collection of Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry. For over four decades Shurbanov has taught English literature at Sofia University and has published a number of literary critical books dealing with the English Renaissance both at home and abroad. He is the winner of a number of prestigious awards as a writer, translator and scholar.

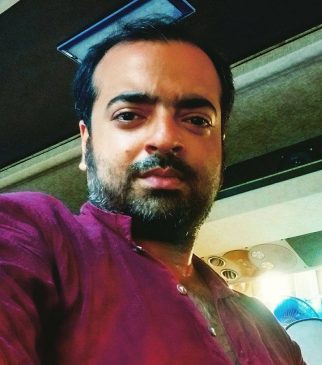

Aritra Sanyal (1983) is a poet, translator. He has authored five books of poems.

Aritra Sanyal (1983) is a poet, translator. He has authored five books of poems.

“I have been lucky to have had good things come my way”

Aritra Sanyal in conversation with Alexander Shurbanov

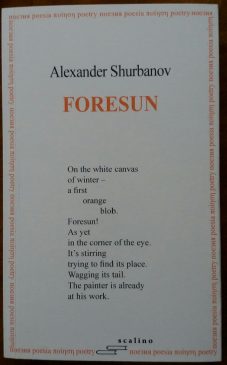

When I first read Alexander Shurbanov’s poem, ‘The Stirring’ –– that is between January- February 2020; the world started showing all the symptoms of the fatality it later contracted. Shurbanov’s poem which appears in his book ‘Foresun’ (2016) runs:

Within the snail’s

cranial shell

the moist tongue of life quivers –

it is already trying

to break through long centuries of dumbness

and to stir out

towards the first vowel of speech

at the far end of the universe.

If life utters a vowel, who is it supposed to utter it for ‘at the far end of the universe’? This pursuit might lead us to several assumptions – different but interrelated. ‘The Stirring’ can be seen as a simulation of the universe itself – where a sound produced is supposed to reach the ‘far end’ but only to remain contained within the periphery – no matter how vast the area is. This interpretation can easily be accepted as the postulate of the process of writing – which is nothing but a poet’s or writer’s attempt at gaining a deeper understanding of the self. Read in this light, the poem presents the image of the universe itself – the one which is trying to comprehend itself through breaking the tranquility of the age-old dumbness with the utterance of a vowel sound.

Therefore, we can posit that a universe is placed within the process of writing, where all chaos is contained with innumerable possibilities. We can picture chaos as half the Amazon rainforest burned to ashes, or as despots ruling the states all across the world; or as protests against state-sponsored terrorism resulting in bloody turbulence in the streets; or as the helpless question mark punctuating the future of the immigrants or refugees; or maybe as the entire world zipped into a lockdown to put a shield against a virus. ‘The Stirring’ philosophically vouches for a poet’s commitment – not to the society, for that matter – but to the infinite self which bears all the subtlest of connections with everything under the sun.

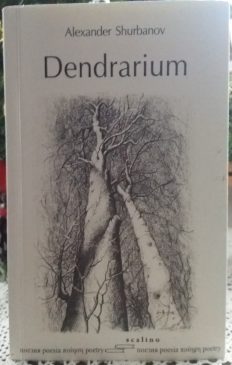

Shurbanov’s other book ‘Dendrarium’ (2019) is rooted firmly in his profound involvement with Nature – especially, trees. The book begins with a statement: ‘I am at peace with trees…’ The poet is capturing various small fleeting moments, taking notes to prepare a commentary on the stillness of the earth’s inhabitants. The poems here sustain an apparent calmness to stylistically complement the inherent nature of trees – though at times that calmness appears confined to the surface – and they exude an empathy that binds the earthlings together. Taking the poem titled ‘The Moment’, we can do a close reading into the dynamics of the relationship between the man-made civilization and the trees. The theme goes beyond the tradition of the Nature poetry by the Romantics, at the same time deviating from it

The road by the railway is still white,

and the birches – a ghostly rush of vertical

sleepers –

gleam in the thickening woods,

but heaven’s eye grows turbid, discoloured.

For a brief moment an unplastered house

faraway among the darkling pines

flares up in crimson flame –

as though it were the dying sun itself.

The poem recounts the experience gathered from looking outside the window of a speeding train. Seen from there an unplastered house in a flicker among the white woods makes the poet think of the dying sun. This imagery can be seen as a clue to Shurbanov’s inclination to translate the image of a universe with the elements he is surrounded by, within the very parameter of the coexistence. In this conversation, while speaking of the nature of translational works, Shurbanov alludes to renowned Bulgarian poet, Atanas Dalchev. In Dalchev’s view literary translation is a window in which things one can see in the street are mixed with the reflections of objects in the room. It will not be wrong to state ‘The Moment’ unravels the process of writing which includes the basic act of translation: the idea of the dying sun, the cosmos is emanating from the poet’s mind itself and is being reflected on the scene captured from the speeding train. It is nothing but life’s attempt to utter a sound for the universe.

In the conversation, I tried to set my primary focus on the profile of the poet and the somewhat audaciously long questions should be excused as the desperate measures taken by me to read in my terms the impact of his oeuvre. Though there is an extensive discussion on his translational works, translation theories – as he translated Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, and Dylan Thomas. In this process, I have to admit I have downplayed Shurbanov’s role as the translator of Rabindranath Tagore fearing the cultural relevance it fetches him in India could have overcast the entire dialogue. My initial hesitation of not being able to read the poet in his original language was creeping in as I started this conversation, though the poems included in ‘Foresun’ and ‘Dendrarium’ are translated by Shurbanov himself. In reply to a persuasive question on translating one’s own poems he said something that with a the legitimate claim can demystify our general confusion about reading great texts in translation: If a poem is not strong enough to survive this transition between two languages and cultures without sustaining irreparable damages it does not deserve to be translated and should remain for local consumption only.

Aritra Sanyal

Kolkata, August 2020

As I regret my helpless condition of being not able to read you in original, I prefer to start the conversation from this very point – in ‘A Note to the Reader’ section of your book ‘Foresun’ you said: “The very essence of translation is partial betrayal of the original motivated by the noblest of reasons”, explaining further how the originating point of a poem starts getting dislocated in the elaborate journey from one language to the one the poetry is being translated in. That poem, needless to mention, also encounters the risk of an active intervention of the translator. Seen from this angle, does not our introduction to the world literature face a big question mark? My knowledge of Vladimir Mayakovsky, Dante Alighieri, Arthur Rimbaud, Pablo Neruda, to name a few, largely depends on how their works were presented by the translator. Though we cannot directly experience what linguistic innovations texts like – A Cloud in Trousers, Inferno, A Season in Hell, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair – introduced to the tradition of their respective languages, we can easily understand, seeing the wide acceptance across the globe, that these are great texts. Question now is: does it mean the intricate linguistic negotiations of a poet with his literary tradition, which can barely be translated; is not a basic requirement of a great text? As you are a poet who has translated others, and your own works, the question I guess unfolds in three different stages…

Yes, indeed, a poem, no matter how free and independent of context it may be deemed, is always inscribed within a local socio-historical, literary and linguistic tradition, and when extricated by the enforced re-birth of translation, its severed umbilical cord remains inexplicably dangling in the new, brave yet foreign world.

This is perhaps the most obvious injury caused by the intercultural transference. But there are other, concomitant ones, which are no less serious, although the receiving audience is not so keenly aware of them. To start with, the semiological nets of different languages, which endeavor to catch the whole of reality, are so disparate that there is no one-to-one correspondence between their constitutive links. Words and phrases supposed to carry much the same dictionary meaning on either side of the linguistic boundary turn out to be dragging behind them hosts of uncongenial connotations. Consequently, even the most expert rendition is bound to thwart the message of the original work.

However, the truly formidable constraint of translation lies deeper than these, for it inheres in the very nature of the language of poetry. Whereas in most other discourses, words are used merely as signifiers, here they function as tangible material objects with clearly manifested characteristics, such as size, acoustic composition, accent, etc. These traits allow them to form associations of sensuous kinship, thus creating the very structure of the poem and ensuring its intuitive impact. As the translator is compelled to deal with an entirely different set of words in the target language, the reproduction of this sensuous effect is next to impossible. It is for such reasons that Robert Frost has said: “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.”

Viewed in this way, the situation is pretty hopeless. And yet, we cannot imagine a world in which poetry is confined withing national domains. We all want to share the heritage of Keats and Baudelaire, of Basho, Omar Khayyam and Tagore, of Yeats and Neruda, as well as the work of our contemporaries. Poets have continued to translate each other across seemingly impenetrable divides. The losses in this traffic are inevitable, but the occasional miraculous achievements of adequacy combined with aesthetic perfection, however rare, have not ceased to give impetus to this ongoing effort, year after year and century after century.

Anyway, the product of translation does not belong either to the author of the original or to the translator: it is always a collaborative work of both. A renowned Bulgarian poet, Atanas Dalchev, remarks that literary translation reminds him of a window in which things you can see in the street are mixed with the reflections of objects in the room. We should therefore not delude ourselves that, by reading a translation we get acquainted with the original in its unadulterated form.

Doesn’t the concept of ‘collaboration’ related to translation become even more interesting when we see a poet translate her/his own works? I take in consideration the two books authored by you: Foresun (2016) and Dendrarium (2019). Apparently, it is you who translated them into English. Question is – who really translated them – You or the other you?

It is me, of course, although I do my best to distance myself from the poems and treat them as separate from and independent of me. The difference in my approach as a self-translator is that I no longer feel free to add to or subtract from or modify the texts in any significant way. I know that I am now engaged in a process of reproduction rather than of production. From time to time, it is true, I also feel an apprehension that the readers of the English-language versions of my poems will be handicapped by their lack of familiarity with their Bulgarian context and therefore may misinterpret some images and implications. But even so, I don’t think I am entitled to add intratextual explanations for the sake of greater clarity. If a poem is not strong enough to survive this transition between two languages and cultures without sustaining irreparable damages it does not deserve to be translated and should remain for local consumption only. In other words, what I have said amounts, I believe, to the following answer to your question: for better or for worse, in both capacities as author and as translator of my own stuff I am still the same I, only my freedom of action is curtailed in my latter function.

It is me, of course, although I do my best to distance myself from the poems and treat them as separate from and independent of me. The difference in my approach as a self-translator is that I no longer feel free to add to or subtract from or modify the texts in any significant way. I know that I am now engaged in a process of reproduction rather than of production. From time to time, it is true, I also feel an apprehension that the readers of the English-language versions of my poems will be handicapped by their lack of familiarity with their Bulgarian context and therefore may misinterpret some images and implications. But even so, I don’t think I am entitled to add intratextual explanations for the sake of greater clarity. If a poem is not strong enough to survive this transition between two languages and cultures without sustaining irreparable damages it does not deserve to be translated and should remain for local consumption only. In other words, what I have said amounts, I believe, to the following answer to your question: for better or for worse, in both capacities as author and as translator of my own stuff I am still the same I, only my freedom of action is curtailed in my latter function.

While we ask this in respect of the change you experience in the process of editing the two versions of the ‘same’ text, I am tempted to add another layer to the question by quoting the poem titled ‘Kingdom’ from Dendrarium: Above the year-old fir saplings/ a thistle towers royally/ with its emerald mantle,/ its purple crown./ This reign/ won’t last long. If I want to express my appreciation in the most precise way, I will say, even though one will notice the title ‘Kingdom’, and the words; ‘royally’, ‘crown’, ‘mantle’ before reaching the last two lines, it is the last two lines that renders the poem a kind of emancipation that allows it to have a world-wide relevance in terms of global socio-political scenario. In ‘The Task of the Translator’, Walter Benjamin says, “Translatability is an essential quality of certain works, which is not to say that it is essential for the works themselves that they be translated; it means, rather, that a specific significance inherent in the original manifests itself in its translatability.” Would you say seasonal efflorescence seen in terms of a political narrative holds the crux of ‘translatability’ here? Moreover, while talking about translation, Benjamin discusses the concept of ‘afterlife’ in the same book: “…a translation issues from the original-not so much from its life as from its afterlife. For a translation comes later than the original, and since the important works of world literature never find their chosen translators at the time of their origin, their translation marks their stage of continued life…” Is the ‘Kingdom’ we read in English the afterlife of the original text?

The fact that an author can dare to translate his own poems into another language (and Tagore has done this before me) problematizes Benjamin’s theory about the need for translation to appear considerably later than the original. Of course, Benjamin seems to be concerned primarily with the translation of classical literature. The notion of “afterlife” in his theory, I must confess, strikes me as rather dark and ambiguous. And, in general, I prefer to think of translation not in philosophical but in practical terms.

As for my “Kingdom” poem, it is indeed a kind of political allegory, but I am not sure if what I have tried to say in it comes through. Seasonal efflorescence, as you put it, is important for this poem, because it supplies the thistle with its sensuous éclat and gives it a grand royal appearance. But it is not so much the plainness of young saplings that I try to contrast this with. The more essential idea that the poem strives to suggest is that the superiority of the thistle which now towers above the trees is short-lived because it will soon sink in their shadow as they grow to attain their mature stature. I wonder though if this suggestion is conveyed unequivocally. As a writer of poetry, I tend often to be too laconic and my intentions remain insufficiently clear. Sometimes this lack of clarity can render the poem more intriguing and richly suggestive, but in other cases it may make it unduly puzzling. At this point we are faced with the dilemma how much in a poem should be as readily apparent as an open face and how much should be glimpsed at dimly through a veil.

What I am trying to get at is the language your poetry first germinates in. The reason why I ask this is a desire to have your advice in translating one’s own poem. I find a poem based on ideas easier to translate, than a poem with a number of linguistic experimentations in it. But even when I am dealing with this so-called ‘easy’ poem, the fact that I think in Bengali throws an unavoidable challenge. It may sound weird but it is true that I find some words like ‘touch’, ‘love’, ‘feelings’ are not totally what I mean in Bengali by ‘Sparsha’, ‘Prem’, ‘Onubhuti’. These are merely signifiers, though. And somehow it proves poetry does not reside in the framework of the words it uses. The entire problem I address here can be complimented by a beautiful poem you put in Foresun: ON BOTH SIDES OF THE MIRROR /two birds hurl themselves frantically/ at each other,/ hitting the glass with their breasts,/ thrashing at it with wings and beaks,/ yearning to get at each other./ One of them/ does not exist.

Yes, the poem you quote was inspired by something I saw happen in the streets of a far-away town, which struck me as symbolic of many inexplicable experiences in human life. But, as you seem to suggest, although such ideas were not in my mind when I was writing the poem, it could be read also as an emblem of the idea of untranslatability. I expect such basic English words as “touch”, “love”, “feeling” to have direct correspondence in any other language, but I cannot be sure how the respective opposite numbers are used unless I am familiar with the day-to-day employment of that other language by its native speakers. Let us take one of these words, “love”, as an example. In Bulgarian usage the word for love appears much more sparingly than in English. For instance, we would not readily close a letter with the phrase “Lots of love” unless we are writing to someone very dear to us. By the way, we would never address a complete stranger in a formal letter as “Dear Sir” the way it is commonly done in English. In the Bulgarian language, such words have retained their primary meaning and their emotional temperature is consequently higher than it is in English. Such disparities are even more striking with other, less common words. This fact makes it imperative for translators to make sure that they are familiar with the pragmatics of the language they translate into and not rely on dictionary equivalents alone. Words, as Mikhail Bakhtin has pointed out, live not in dictionaries but on the lips of those who speak them.

Yes, the poem you quote was inspired by something I saw happen in the streets of a far-away town, which struck me as symbolic of many inexplicable experiences in human life. But, as you seem to suggest, although such ideas were not in my mind when I was writing the poem, it could be read also as an emblem of the idea of untranslatability. I expect such basic English words as “touch”, “love”, “feeling” to have direct correspondence in any other language, but I cannot be sure how the respective opposite numbers are used unless I am familiar with the day-to-day employment of that other language by its native speakers. Let us take one of these words, “love”, as an example. In Bulgarian usage the word for love appears much more sparingly than in English. For instance, we would not readily close a letter with the phrase “Lots of love” unless we are writing to someone very dear to us. By the way, we would never address a complete stranger in a formal letter as “Dear Sir” the way it is commonly done in English. In the Bulgarian language, such words have retained their primary meaning and their emotional temperature is consequently higher than it is in English. Such disparities are even more striking with other, less common words. This fact makes it imperative for translators to make sure that they are familiar with the pragmatics of the language they translate into and not rely on dictionary equivalents alone. Words, as Mikhail Bakhtin has pointed out, live not in dictionaries but on the lips of those who speak them.

The openness of poetry usually allows readers to see reflections of their personal thoughts and experience. As a poem ‘Kingdom’ is suggestive, to be exact; it helped me have my own interpretation of it – no matter how limited the understanding is. When I started reading ‘Dendrarium’, half of the Amazon has already reduced to ashes – Australian wildfire killed thousands of animals – Greta Thunberg rose to be a global icon with the most meaningful popularity. The entire book shows a profound concern for Nature – or in a broad sense, for Life in its true sense – a thing we need now in 2020. If I am allowed to quote a poem from the book: A STALWART WHITE-BARKED TREE./Snapped in two by old age or a storm. Or both./ Propped with half of its branches on the ground./ Half-upturned. At the edge of the forest. Catches/ the eye. For an instant. As the train whizzes by. The deep empathy a reader experiences here or the quirky blend of humor in the anticlimax of the poem BLACK SHADOW: High up/ among the bare branches/ a black shadow dangles./ A crucified bird!/ Or a plastic bag? – convey a message to humanity. ‘Dendrarium’ helped me look at the entire world affair from the perspective of poetry and I am proud to confess my reaction to ‘Dendrarium’ was to some extent influenced by the consciousness about the emergency we survive. Similarly, the last two lines of the poem Kingdom: This reign/ won’t last long… gravitated all my attention to echo my resistance to the pathetic political condition in my country. Poems gain, shed, change their implications according to the circumstances – time and social context. Sharing Kingdom in social media I voiced my protest recently. In the stranger soil the tree had a new meaning.

A poem starts its life’s exciting journey in the author’s mind but at its birth is released into a wider world in which its personality will gradually grow and develop. Parents do not possess their offspring. They can only observe its course at an ever greater distance with hope and trepidation. And they must be happy and grateful when the child happens to enter the company of sensitive and appreciative people who will contribute to the raising of the youngster. In the case of a poem sent by its author out into the world this company consists of translators, critics and an anonymous multitude of silent readers. All of these in conjunction will eventually produce the definitive shape of the poem or the sum of its shapes. But the possibility for these shapes to emerge must be contained at the core of the poem from the moment of its creation. Just like us people, some poems have more varied potentials than others, and like people again, some are more focused and purposeful, while others are prone to indulge in surprising diversions. But I believe that nothing can be added to a poem that has not been already there as a germ at its inception.

A poem starts its life’s exciting journey in the author’s mind but at its birth is released into a wider world in which its personality will gradually grow and develop. Parents do not possess their offspring. They can only observe its course at an ever greater distance with hope and trepidation. And they must be happy and grateful when the child happens to enter the company of sensitive and appreciative people who will contribute to the raising of the youngster. In the case of a poem sent by its author out into the world this company consists of translators, critics and an anonymous multitude of silent readers. All of these in conjunction will eventually produce the definitive shape of the poem or the sum of its shapes. But the possibility for these shapes to emerge must be contained at the core of the poem from the moment of its creation. Just like us people, some poems have more varied potentials than others, and like people again, some are more focused and purposeful, while others are prone to indulge in surprising diversions. But I believe that nothing can be added to a poem that has not been already there as a germ at its inception.

To come down to my own poems collected in Dendrarium, they seem to me to be first of all a loving observation of and communication with the living world of nature which surrounds us and infuses its vitality into us. Yet, this poetry is not devoted to the construction of an idyllic environment, an escape from the human world into the wild. On the contrary, the problems and concerns of the society in which we live continue to crop up at every step in this book, for there is really no gap between the natural and the political dimension of our existence. They are intimately interwoven and mutually dependent. And in this close association they often begin to resemble and reflect each other. Aristotle’s definition of man as zoon politicon suggests the duality of human nature: unlike other animals, we participate in an unceasing collective effort that drives history forward, yet, for all that, we are still nothing else but zoa, part and parcel of the world which has given us existence. And if we become oblivious of this truth, we shall surely destroy ourselves.

You have been active as creative person, more specifically as a poet across a number of decades that witnessed the world we inhabit fight different crises. How has your idea of poetry changed, or evolved under the influence of the constant change in Time?

A poet is not a journalist. Rather than reflecting directly developments in the world surrounding them and reacting to these developments, poets seem to follow their destined way largely untroubled by external events, immersed in what they carry within from childhood to death. Yet, in an oblique manner, the reality of their historical period inevitably influences and models their creative career. In my case, I started writing poetry as soon as I learned the alphabet. And throughout my adolescence my poems were songlike, cheerful and sonorous. Needless to say, they were still quite unskillful and naïve. This phase continued into my early twenties, though during the interim I was experiencing different influences and accumulating practice. My second period, lasting three long decades of living and working in the conditions of Soviet-style socialism, is marked by attitudes of increasing disenchantment and skepticism as well as by a gradual departure from rhymed poetry to free verse. The latest period, since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the return of Eastern Europe to capitalism, is largely characterized, I guess, by lyrical introversion and a quest for a new set of lasting values. This self-reflexive account is entirely subjective and improvised though, I hope, not untrue. And the development I have sketched out above is certainly shared by other poets of my generation, so it must be the consequence of larger social changes, which have shaped our little individual lives.

We are very curious to know about your experience of the second phase: by that time you have taken writing as a serious vocation; and a major shift in the style of self expression occurred. But that, you said, resulted from disenchantment. In what ways that Soviet-style socialism became the cause of the bitterness? This is not a very sound political statement I am going to make; but it is true, the socialism is a part of the fancy, the romanticism of many people struggling to survive this capitalism. I see a large section of protestors fighting back the atrocities by the state dream about a reboot of the total system of the society…

If I may quote Atanas Dalchev again, he says the following: “With a bullet you can kill a man, but not an ideal. There is only one means by which you can destroy an ideal and that is to let it materialize.” The ideal of a society based on equal opportunity and cooperation is beautiful and it is irresistibly attractive, especially if you are young and idealistically minded. There were quite a few people in Bulgaria who were fired with the socialist ideal at the end of the Second World War, for my country wasn’t affluent and the contrast between the rich and the poor was sharp. Under Soviet instruction and control, however, the national transition from capitalism to state socialism was bathed in blood at its very start. And very soon the ideal of equality was reduced to a hollow façade. An Orwellian discrimination between those in power and the ordinary people took place and we were forced to live in a world of hypocrisy, in which the accepted public language was full of enthusiasm and optimism while the reality around us was increasingly depleted of hope for a better social arrangement. To raise your voice against the official lie meant to condemn yourself to virtual non-existence, though not necessarily to physical annihilation. Most of us weren’t born to be heroes and while we did not oppose the government in any radical way, we chose not to speak and write the words dictated to us. Our writing gradually became skeptical, ironic, dissonant. It was a matter of taste not to comply, as Zbigniew Herbert proudly declared. Consequently, it became difficult for us to publish our own stuff. And some of us turned to translation as a substitute. Those were the glorious days of translation and of thus acquiring free expression by indirection. “Aesopian language” we called it.

I know that socialism will continue to attract honest people troubled by the obvious wrongs of capitalism all over the world and the hope that a better solution of human problems can be achieved will never die, but, like Mahatma Gandhi, I believe that the moment you taint an ideal with violence and bloodshed, even if you do so in the name of sanctity, you destroy it. And yet, without the use of force no real change can be achieved. This is the great conundrum we are faced with. My own political acumen is too weak to overcome it. And also, for a true socialist order to succeed you will need a totally different human race, selfless, considerate, altruistic, noble. The way things are, however good your intentions may be, you are bound to end up in the bathos of Animal Farm.

You have translated classics, somehow these works were born into Bulgarian words and culture through your active mediation. Which text threw the toughest challenge to you? Has the process of translation affected your diction in Bulgarian?

Unsurprisingly, the most difficult problems I’ve had to cope with as a translator of classics, were sprung on me by Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, which I grappled with for five long years in the late 1970s. I had to coin a Bulgarian poetic language that could recreate the operatic solemnity of Milton’s Latinized diction. And I had to be very cautious about the adequate rendition of a dense network of biblical and antique images or allusions enveloping the entire poem. My most radical and daring decision with respect to the form of the translation was to extend the original five-foot meter to a seven-foot iambus so as to accommodate in this larger measure the generally longer Bulgarian words and phrases without sustaining significant losses of meaning.

To your second question now. I have always tried to keep my own poetry apart from my translation and I think there is very little kinship between these two departments of my poetic output, both in contents and in form. I have cultivated this distancing deliberately, for fear that a less strict division might result in a mutual contamination diminishing the authenticity of the two separate activities. But as I am one person rather than two, some influences across the demarcation line are all but inevitable. My hope is that whatever cross-fertilization has occurred is at the deepest and least obvious levels of text-composition. One thing I have no doubts about: the work of translation, if it is conscientious enough, makes a writer more careful in her/his dealing with words.

You translated Chaucer. Medieval English has a stark difference from the style used by John Milton. Shakespeare’s English can in no way be compared to the one of Dylan Thomas. Was there any way to record in translation how the original language of the texts changed its nature?

Quite right, Chaucer is further removed from us in time and in language than even the early modern writers. But he strikes me as closer to us in his dealing with human psychology and his response to the environment than more recent authors. In a way, Chaucer is more direct than his successors, less inhibited by courtly fashions, by the rules of decorum, etc. So, the translator ought not to introduce unnecessary filters between the works of this poet and their new readers. Nonetheless, some signals of the passage of time would be in place. I have sprinkled my translation of the Canterbury Tales with slightly archaic words and turns of phrase reminiscent of earlier Bulgarian writers, at the same time trying not to overdo it. My more important concern has been to achieve a temporal neutrality of diction steering clear of the more modern elements of the language. The same goes for translations of Shakespeare or any other writer of the distant past. Of course, various historicisms, such as references to specimens of medieval weaponry, objects of everyday use, etc., as well as antiquated forms of address, date the text quite unequivocally and their presence should not be blurred in translation. Yet, translators ought to keep in mind that they are addressing their present-day audience in the way Chaucer or Shakespeare were addressing theirs and therefore an overly archaization of the new text would falsify the strategies of the original. It would also shorten the life of the translation by exerting a backward linguistic pull rather than a forward drive.

Quite right, Chaucer is further removed from us in time and in language than even the early modern writers. But he strikes me as closer to us in his dealing with human psychology and his response to the environment than more recent authors. In a way, Chaucer is more direct than his successors, less inhibited by courtly fashions, by the rules of decorum, etc. So, the translator ought not to introduce unnecessary filters between the works of this poet and their new readers. Nonetheless, some signals of the passage of time would be in place. I have sprinkled my translation of the Canterbury Tales with slightly archaic words and turns of phrase reminiscent of earlier Bulgarian writers, at the same time trying not to overdo it. My more important concern has been to achieve a temporal neutrality of diction steering clear of the more modern elements of the language. The same goes for translations of Shakespeare or any other writer of the distant past. Of course, various historicisms, such as references to specimens of medieval weaponry, objects of everyday use, etc., as well as antiquated forms of address, date the text quite unequivocally and their presence should not be blurred in translation. Yet, translators ought to keep in mind that they are addressing their present-day audience in the way Chaucer or Shakespeare were addressing theirs and therefore an overly archaization of the new text would falsify the strategies of the original. It would also shorten the life of the translation by exerting a backward linguistic pull rather than a forward drive.

As translator, I have always appreciated the chance of turning from one poet to another, radically different from the previous one and accepting the challenge of reforming my approach to language, to imagery and ideas, almost becoming a new person. I suppose, daring actors, who are not content to impose the same personality on every new role, have experienced this joy of the protean artistic self.

It is a rare opportunity for a Bengali to talk with the translator of Tagore. Though as a race we are totally full of him – the songs he composed, the plays, stories, even a particular dance format – everything surrounds us. He has become the integral component of our culture and society; and he is popularly called as the ‘World-Poet’ (Vishwa Kobi). But does Rabindranath Tagore survive with relevance in the world map? The question haunted us until now, when a few days ago, Martin Sheen, a Hollywood star, staged his protest reciting Tagore’s much feted poem: Where the mind is without fear… this undoubtedly will result in a wave of instant internet search across the globe, but we are not talking about that popularity. In Tagore, Portrait of a Poet, Buddhadeva Basu, the only eminent critic the Bengali literary tradition ever had, summarizes ‘Tagore’s trouble’ saying that unlike Goethe, Tagore does not make us wiser, rather he awakens in us new sensibility. Moreover, absence of the single master-piece in his oeuvre, the single work that ‘contains him so to say, on which we can lay our hand and say we have him’… makes him a difficult figure to be represented in the world map in totality. We will like to have your comments on Tagore.

Tagore is perhaps the most internationally contextualized Indian poet. My father as a youth had been in the crowd struggling to squeeze into a Sofia theatre where Tagore was going to give a public lecture during his visit to Bulgaria among other European countries almost a full century ago, in 1926. Some of his works had already been translated into our language and he was received with adulation, like a prophet, a figure he suggested with his impressive figure and his attire. My first encounter with Tagore’s work in translation was in my school years when I came by chance across his novel Gora and was fascinated by the atmosphere he created in it, so familiar from our own largely patriarchal life in the middle of last century and yet so excitingly different. It struck me as such a poetic book. Later on, when I got acquainted with his poems and his philosophical essays, I thought I knew what to expect, but his concern for the global future of all humanity and his strong belief that we all must work together for the preservation and the betterment of our world as a complex biosphere was contagious. I was offered to compile and translate a large representative sample of a few hundred poems of his for a jubilee multivolume edition which was published in 1985 complete with a special address to the Bulgarian readers by the then Prime-Minister of India, Indira Gandhi. My translations were done from the English-language version of Tagore’s poems, for the most part created by the author himself and thus figuring as a second original. When I was invited by the Indian government to visit your country and tour around the Tagore places in Bengal during the next year, I had the unforgettable experience of listening to the poet’s works in their original language, as they were sung to me by the charming wife of a friend of mine at their hospitable home. My pleasure was immense. I can only hope that someday Tagore’s poetry will be translated directly from its pristine Bengali form. At the same time, I am a little doubtful about the possibility of recreating this form in a way that can have the same impact on people used to an entirely different poetic tradition. Tagore’s decision to divest his poems of their close-knit formal patterning resembling his native folksongs while translating them into English was very wise, for in this way he allowed their rich texture of ideas and images to reach the new audience unhampered by an exotic dress. This poet’s message is universal and its passage to all cultures should be made possible.

Tagore is perhaps the most internationally contextualized Indian poet. My father as a youth had been in the crowd struggling to squeeze into a Sofia theatre where Tagore was going to give a public lecture during his visit to Bulgaria among other European countries almost a full century ago, in 1926. Some of his works had already been translated into our language and he was received with adulation, like a prophet, a figure he suggested with his impressive figure and his attire. My first encounter with Tagore’s work in translation was in my school years when I came by chance across his novel Gora and was fascinated by the atmosphere he created in it, so familiar from our own largely patriarchal life in the middle of last century and yet so excitingly different. It struck me as such a poetic book. Later on, when I got acquainted with his poems and his philosophical essays, I thought I knew what to expect, but his concern for the global future of all humanity and his strong belief that we all must work together for the preservation and the betterment of our world as a complex biosphere was contagious. I was offered to compile and translate a large representative sample of a few hundred poems of his for a jubilee multivolume edition which was published in 1985 complete with a special address to the Bulgarian readers by the then Prime-Minister of India, Indira Gandhi. My translations were done from the English-language version of Tagore’s poems, for the most part created by the author himself and thus figuring as a second original. When I was invited by the Indian government to visit your country and tour around the Tagore places in Bengal during the next year, I had the unforgettable experience of listening to the poet’s works in their original language, as they were sung to me by the charming wife of a friend of mine at their hospitable home. My pleasure was immense. I can only hope that someday Tagore’s poetry will be translated directly from its pristine Bengali form. At the same time, I am a little doubtful about the possibility of recreating this form in a way that can have the same impact on people used to an entirely different poetic tradition. Tagore’s decision to divest his poems of their close-knit formal patterning resembling his native folksongs while translating them into English was very wise, for in this way he allowed their rich texture of ideas and images to reach the new audience unhampered by an exotic dress. This poet’s message is universal and its passage to all cultures should be made possible.

Can there really be subdivisions like love-poems, war poems, and political poems? How can a poet immediately react to the recent worldwide conundrum? Or better I should ask, is it mandatory to pen down something instant as a tip to protest or solidarity?

I have already said something about my non-journalistic, introspective reaction to social and political developments. The best examples of Bulgarian poetry, even from the periods of violent revolutionary struggles involving the entire nation and its poets in the first place, demonstrate a wonderful symbiosis between the personal and the public. I believe that the most powerful political poetry is the one that issues from a bleeding heart. In this sense, it would be wrong to try and compartmentalize poetry into thematic divisions, though such classifications are made again and again. My own anthology dedicated to trees, for instance, could be described as a poetic book about nature, but it is, of course, also about love and politics and life and death. Poetry is never confined to a single topic, like an essay; its movement is centrifugal and its ambition is all-encompassing.

What is your favourite time of the day for writing?

Well, when I am up to it, I feel I am most capable of writing between say ten in the morning and six in the evening, in the full light of day. But a poem often descends on me unexpectedly when I am already in bed after midnight, and at such times it always has priority over sleep, even if it should take hours to compose. Poems, in fact, surprise me quite frequently as I walk in the street or across a park and then I feel lucky if no acquaintance bumps suddenly into me, nor do I have to rush to an important meeting or appointment. Once the birth of a poem is interrupted, like the birth of a child, it cannot be resumed.

We will like to have a brief profile of the Bulgarian literary tradition from you. Who according to you are the most promising ones?

When I was young, it wasn’t easy for a budding Bulgarian poet to make his or her debut. I first tried to publish a book when I turned twenty-three but it was not to happen until ten years later and even then it was in a collective volume of a dozen authors grouped together. At that time, all publishing houses in the socialist countries were owned by the state and closely monitored by the ideological authorities. Young poets were expected to write as the mouthpieces of society and their stuff had to be cheerful and optimistic. Now it is a totally different ballgame for the present-day young. There are plenty of independent publishers to choose from and you can get your poems unto print without any interference from the outside, especially if you are prepared to cover some of the production costs from your pocket. This is a great change for the better, of course. The downside of the new setup is that the quality of such publications is very uneven and it is not easy to sift the good books from the plethora of bad ones. There is little serious criticism and very few literary periodicals capable of providing advice and cultivating the taste of inexperienced readers. The new ease of going public makes some of the authors rather sloppy and uninterested in perfecting their craft. I am not sure I have read all the young poets worth reading, yet I would certainly recommend the work of Ivan Landzhev, Vladislav Hristov, Stefan Ivanov – perhaps a few others, but I hesitate to make a longer list. Let’s wait a little longer. Poetry is not a hurried business.

What will be your advice to a young poet?

If asked twice, I would say: Write only from your heart, not from the mind, though not mindlessly. And write the poem so as if it were a note to yourself, not a public oration designed to impress and captivate an impersonal audience. As John Stuart Mill puts it, “eloquence is heard, poetry is overheard”: allow the others to overhear the poetry, which you address to yourself. Only then will it take effect.

But don’t you think the advent (or invasion) of the online-based platforms (social media) where people can express themselves ‘freely’, has eradicated the concept of editing? It is of course a threat to the ‘high culture’ – does not matter whether one is sympathetic to the privileges of a few in this respect. It is true, on the other hand, this tendency, with the foil of a ‘democratic right’ for everybody has dismantled standard magazines form their positions in general psyche.

Yes, this liberation from constraints creates in the younger generations a sense of absolute freedom, and absolute freedom is always a dangerous drug. True art can flourish only along the borderline between freedom and discipline. And discipline is always harder to cultivate than freedom. The ideal literary setup is the one in which there are at least a few respected journals, each edited by a good critic and forming a hardcore of regular contributors with aesthetic orientations consonant though not identical with those of the editor. There had been such publications in Bulgaria before the socialist revolution but, sadly, one would look in vain for such life-giving centres of literary life now. They are largely replaced by electronic substitutes, whose existence is somewhat ghostly, elusive and unreliable.

Is print media dying?

I don’t really know. On the one hand, bookshops are burgeoning everywhere and their rapidly expanding shelves spread out in multi-story complexes can hardly accommodate all the new books and other printed matter which flow continuously from the publishing houses. On the other hand, an increasing amount of texts is poured into the digital sphere, which gradually becomes self-sufficient. Even I, in my advanced age, can no longer imagine my everyday existence without a Kindle electronic reader, which is constantly on my bedside table and with its amply lit screen is a blessing for my failing eyesight. It’s all very well that we have acquired these new means of reading the written word and we may soon leave behind the printed-book culture just as we have long left behind the manuscript one. The present expansion of great bookstores may turn out to have been just the final inflation of a balloon before it bursts. My worry is that humanity is entering into a dreamlike, impalpable reality, which may also burst someday leaving no trace of its existence. Previous civilizations have disappeared indeed but not without a trace. They have left behind words, thoughts, beliefs, images recorded on stones, clay tablets, papyruses, parchments, paper – all preserved in legible signs for us to decipher and appreciate. These material objects have survived floods, wildfires, earthquakes and formidable climate changes and have come down to us with their meaningful and exciting messages. But what may happen to our own culture entrusted in its entirety to the ghostly offices of the Web if a minor global disaster befalls us and deprives us of electricity and of the use of all our precious electronic gadgets? Where will our modern heritage be salvaged for posterity? Perhaps in an invisible digital cloud, released to float through the outer space like a shipwreck’s bottle thrown into the ocean with the vague hope that it may arrive intact on a distant coast inhabited by appreciative intelligent beings? Perhaps…

How can influence help a young poet?

Influence is all but inevitable at the early stages of poets’ training for their job. And it is not something that should be shunned. Just as a young painter or sculptor must do their apprenticeship in the studio of at least one distinguished master, trying to do things the way he wants them done and to imitate his characteristic techniques to the last detail, a would-be poet should pass through the schooling of established masters. But the sooner you get through this phase of your development and out of it, the better. To remain someone’s disciple for life is to become an epigone, a replica of another personality. Some of the influences you have experienced in your youth are going to stick to you to the end, though they won’t be your distinctive, dominant features any more. That is why it is important for every beginner to choose their models carefully, for they will remain with them for life. A pupil from Verrocchio’s school will bear throughout his career Verrocchio’s recognizable imprint. To rise above that you have to be a Leonardo. The most fortunate artists are those who pass through a number of different schools without forgetting who they really are.

If you want to say about your current projects…

Projects are for the younger. Instead of a project, I have a prayer: to be reasonably healthy, both physically and mentally, as long as I am alive. And in general, I have never been ambitious about planning for the future. I have preferred to wait and see what comes my way, what would like to befriend me, and if I like it too, then something may happen. I must say, I have been lucky to have had good things come my way. Hamlet’s final wisdom is simple: “The readiness is all.” Now I slowly gather new poems for my next book. None of that has been planned in advance and I am still not sure what this book is going to look like. But one thing is sure: it will be mine. Or rather, it will be me freed from myself.

And what are you reading now? Any recommendations for us?

I’m not sure how religiously I follow the ancient injunction for all artists, Nulla dies sine linea, but I can never finish a day without leafing through the pages of a printed or an electronic book. Right now, I am into Shlomo Sand’s fascinating survey, The Invention of the Jewish People. And in general, I love conceptual and essayistic history books, such as Russell Shorto’s Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City, Richard Holmes’s The Age of Wonder, Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman, A. Scott Berg’s Wilson, Alice Albinia’s Empires of the Indus, Anne Applebaum’s Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, Svetlana Alexievich’s Chernobil, as well as books about the lives of famous writers like A. Scott Berg’s Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, Susan Cheever’s E.E. Cummings: A Life, Salman Rushdie’s Joseph Anton: A Memoir, etc. I’m also attracted to books about nature written by competent and experienced naturalists like Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees or Terry Masear’s Fastest Things on Wings. I also read fiction, though more sparingly. Lately, I have been particularly impressed by Colm Toibin’s novels (especially, The Master), Ian McEwan’s Machines Like Me… and My Purple Scented Novel, Dave Eggers’s The Circle, John Willams’s Stoner, Taiye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go, several books by a younger American writer, Joshua Ferris, and so on. I am also trying, for the umpteenth time since my younger years, to cross the vast philosophical sea of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason with the rickety rowboat of my inadequate intelligence. I can at least fathom the depth of his thought without being fully aware of the vast life heaving under the surface. Well, I do recommend all the books I have mentioned to those who haven’t as yet chanced to come across them. Of course, I also try to keep abreast of new literary developments at home. I have already mentioned my favourite younger Bulgarian poets. Of the novelists I like most of all Milen Ruskov and Kerana Angelova, both of them gifted representatives of the middle generation.

No matter whatever one has achieved as a poet (or as an artist in general), can anyone ever escape the overpowering sense of failure?

I can only speak for myself. As often as a new poem begins to take shape in me, I feel the heavenly elation of a demiurge creating something extraordinary out of nothing. And it appears to me that this is definitely the best thing that I have ever produced. But a few days later, when I return to it with unblurred eyes, I see how pathetically short it falls of the inner image that gave it being. And I am crushed, but then I say to myself: “Oh, what the hell! Next time we are sure to do better.” A similar sense of frustration comes over me as I chance to look back on the whole of my so called “lifetime achievement”. Only in this case I know that there is not going to be a next time.

References:

Foresun, Alexander Shurbanov, Scalino (2016)

Dendrarium, Alexander Shurbanov, Scalino (2019)

Tagore: Portrait of A Poet: Buddhadeva Bose, Papyrus (1994)