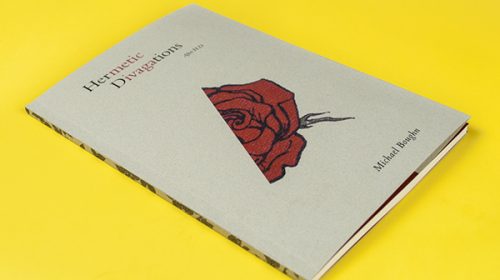

A slowly unfolding rose…yes, that is the cover page of Hermetic Divagations: After H.D., a collection of poetry by Michael Boughn, an USAmerican/Canadian poet, whom I know through his well-known online journal, ‘Dispatches from the Poetry Wars’, he edits with Kent Johnson. The slowly unfolding rose reminds me the line from Ezra Pound’s Canto 106, “so slow is the rose to open”. Question comes into mind, is it symbolizing Pound’s rose or Rose-Croix, the Christian Symbolism? But “After H.D” in the title of the book turns my attention to Hilda Doolittle’s (H.D.) Hermetic Definition, “the reddest rose” of H.D.’s passion, love, though “unseemly, impossible / even slightly scandalous”, continues to unfold. Then I turned to Boughn’s dedication page which shows H.D.’s poem “I did not cheat / nor fake inspiration, / what I wrote was right then, / auguries, hermetic definition….”, a joint sense of “Ancient Wisdom” which includes kabbalah, astrology, magic, alchemy, Christianity, classical and Egyptian mythology mingled with her personal experiences of love, an interweaving between myth and metaphors of multiple cultures and their relevance.

A slowly unfolding rose…yes, that is the cover page of Hermetic Divagations: After H.D., a collection of poetry by Michael Boughn, an USAmerican/Canadian poet, whom I know through his well-known online journal, ‘Dispatches from the Poetry Wars’, he edits with Kent Johnson. The slowly unfolding rose reminds me the line from Ezra Pound’s Canto 106, “so slow is the rose to open”. Question comes into mind, is it symbolizing Pound’s rose or Rose-Croix, the Christian Symbolism? But “After H.D” in the title of the book turns my attention to Hilda Doolittle’s (H.D.) Hermetic Definition, “the reddest rose” of H.D.’s passion, love, though “unseemly, impossible / even slightly scandalous”, continues to unfold. Then I turned to Boughn’s dedication page which shows H.D.’s poem “I did not cheat / nor fake inspiration, / what I wrote was right then, / auguries, hermetic definition….”, a joint sense of “Ancient Wisdom” which includes kabbalah, astrology, magic, alchemy, Christianity, classical and Egyptian mythology mingled with her personal experiences of love, an interweaving between myth and metaphors of multiple cultures and their relevance.

I turned the page and entered into Boughn’s poetic world and was surprised with the form of his poems, where each poem mirrors the form of its analog in H.D.’s Hermetic Definition, having the same three lines stanzas. In case of H.D. the secret of structure of the poems may be an interweaving style of many; like her three trimesters period during creative pregnancy of Hermetic Definition; three pathways of Hermeticism which are alchemy, astrology and theurgical magic; three doors of Notre Dame as H.D. named them, first door for astrology, last door for theurgical magic and the middle door she kept for alchemy which was her judgement for her hopeless passion for love; the Hegelian triad “thesis, antithesis, synthesis” of her conflicting emotions. In case of Boughn’s Hermetic Divagations I was searching for an answer whether this is homage for H.D. Boughn provided an answer at the end of his book, “This constitute a material connection that opens a relationship that is neither homage nor conversation nor explication nor history, but is all those things and more – a kind of grateful thinking brought to attention through her words.” Then I entered into his world of realization,

hunger struck in traffic. Where

the world is, magnitude plays

hide and seek among forgotten

stories of god slain serpents

and wretched earth voice’s pain echo

in rumors of a world. As below

so below reeks of hermetic

deformations, bronze gods

melted for forms

of exchange unaware how

sublimation once breathed hot

life into little token’s death clink

(“Definitions of Entrance”, 1-13)

According to Indian philosophy of Hermeticism, Purusa (pure consciousness) & Prakriti (Nature), there is a continuous cycle of evolution and dissolution which follow each other. In the process of evolution, nature is transformed and differentiated into a multiplicity of objects and Purusa gets bonded to Prakriti for a state of living being. This fusion leads to an emergence of intellect and ego (self-consciousness). The liberation from this bondage arises when discriminate knowledge between conscious Purusa and unconscious Prakriti is realized. In the process of dissolution, the physical existence mingles back into Nature’s five primary elements earth, water, air, fire and space and the undifferentiated primordial substance from its particle reality to wave consciousness and comes back to home, the God.

From the hint of this dualism of matter and consciousness of Hermeticism, Boughn has extended the Hermetic Definition to Hermetic Divagations, a hint of divergence. The poet raises his finger towards the uncivilized war of our civilized world. It’s a new reflection in the mirror of the present on the questions about war raised by H.D. At the very beginning of the poems there is a hint, “Definitions of Entrance”. Whose entrance? During the transcreation of the poems from this book, we had various exchange of thoughts and Boughn wonderfully explained this ‘Entrance’ as, “The poem is concerned with “hidden entrances” (say, from/to spaces of sense beyond the world of general equivalence that we are trapped in) which she, also, was concerned with, and her entrance is the revelation of such an event.” As if H.D. enters herself into the imaginative space of the poet, into the world of deep consciousness beyond the general equivalence of the visible world which is full of outcry of deceased in the debris of destructions. When all our existence shake in the flame of fire raising from the dark corner of war, her secret entrance opens all the questions peeping from the war-vase. And the poet made us to stand in front of the question of freedom formulation of an opaque world.

Then I entered into an interactive session with Michael Boughn about his views on poetry and poetics involved in his process of poem.

Runa: Tell us something about your start of journey in poetry.

Boughn: It was a book I found in my grandfather’s otherwise very meagre library when I was about 12 years old. It was a collection of poems by the poet Ogden Nash. Nash was a genius of frivolity and, I suppose you could say, skylarking with words, taking great liberties with language and having a lot of fun while doing it. His poems about animals are always delightfully inventive:

A cow is of the bovine ilk

One end is moo the other milk

Or The Squab:

Toward a better world I contribute my modest smidgin;

I eat the squab, lest it become a pigeon.

Or this one on chipmunks which ends in an astonishing revelation:

My friends all know that I am shy,

But the chipmunk is twice as shy as I.

He moves with flickering indecision

Like stripes across the television.

He’s like the shadow of a cloud,

Or Emily Dickinson read aloud.

Nash’s delight with language infected me and left me helpless in the face of poetry’s playful seduction. Then, in 1968, I met Robin Blaser and studied with him for several years. He took my love of poetry to the next level when he introduced me to the work of H.D., Pound, Williams, William Blake, and the extraordinary ways in which poems think.

Runa: Is there a relation between the poetic language and the body language of the word? Is a poetic idea revealed in the physical body of the poem? What do your feelings say about this relationship?

Boughn: If I correctly understand your question, my answer is an unequivocal and ecstatic yes. Poetry begins in the deep, circulating, rhythmic senses the body is conceived into. Life begins in a pulsing spot of blood, the pulse and the stuff inextricable from each other, and grows into all the rhythmic vibrations that inform it from inside and outside mother’s body. That rhythmic knowledge feeds poetry’s sounding of the world, it’s measuring. The rhythmflesh yields a particular transformative gnosis that arises out of that sounding of the world resonating in each cell. The head and heart via the ear and the breath, Charles Olson said.

Runa: Poetry is form, or process, or [de-] construction or idol-making – which one of these is closer to your way of writing and why?

Boughn: All of the above, and more. The potential the poem brings to the page establishes the space as a site of freedom, the freedom to create. Anything goes, as long as it works. To create a poem is to compose words, which is to say rhythmic sounds with meanings, into an event, to arrange, to put together a particular ordering of sound/meaning. Sound and meaning both become part of the media the poet has access to as the composing proceeds. Process and form are always immediate, which we learned from the New American Poetry. How to think through the freedom of the poem.

What the poet does with that freedom is up to her. Too often it’s abandoned to the Given in one form or another. Whether that’s a given form, a given “voice”, or a given “theory”, it’s the abandonment of the poet’s responsibility to imagination’s freedom. It’s scary. How can you know what to do without clear precedent? But if you can get through that and find a way to trust the imagination, you can do anything with the words, even as they start to do strange things to you. The only requirement is that it all work, which is how you know a real poet. The composition keeps on meaning further. William Carlos Williams at one point called a poem a small machine made out of words, his point being that it is always a made thing that continues to produce something – meaning? sense? I like to think of the poem as a Thing which recalls the Old High German ding “public assembly for judgment and business.” To goof off Williams, a poem is a thing made out of words.

Runa: Poetry requires space, where the reader participates in the poem while at the same time remains outside it. What is your opinion on this dichotomy?

Boughn: I don’t think I understand this question. To read a poem – and it should be read out loud so that the sonal vibration field literally alters spacetime and the structure of your body – is to enter into its knowledges, to be possessed by them, although never to possess them. I think the best place to be is in the poem. No need to hang around outside.

Runa: Is poetry a search for “reality” and existence, or a search for mystery? Or none of those? Then what is it?

Boughn: The idea that “reality” is something other than mystery is a product of an atrophying disease of the imagination called “sociology.” That’s comes from what Robert Duncan called a World Order defined by a truncated definition of secular determined by the exclusion of something called “sacred” or “divine.” It wants to limit vision to one plane of existence by claiming there is nothing else, nothing further than something called society. But reality is a mystery, isn’t it, finally? Charles Olson proposed our postmodern condition as the secular that loses nothing of the divine, a move to a visionary state or plane beyond the meagre reductions of the sociologists, and the binary mindset.

And poetry is a mode of linguistic knowledge that is uniquely capable of introducing us to that mystery in its incommensurable presence. It is a sounding of the world’s complex depths and folds, it’s mysteries wrapped in its clarities, its clarities nestled in its mysteries. I like Roman Jakobson’s notion of the “poetic function” as the disruption or displacement of the axis of combination to the axis of selection. Even though this ends up visualized as a graph where the two dimensions are vertical and horizontal, the vertical axis of selection is not a transcendence (not that I have anything against transcendence), but an opening into the body of the Word, the ex-posure of mansions of meaning unfolding and resonating in playful resistance to the pull of the combinatory force rushing from word to word to reach the end of words. Poetry is not interested in the end of words. The wild love of words proliferates throughout the axis of selection, dancing in a sea of sense until landing on a word that is the exact calculation, and that will continue to resonate with the others, precisely destabilizing meaning. Suspending combination leads into the wild proliferation of potential sense, overtones and undertones resonating around the exact calculation of the particular manifestation of the mystery in one word.

Runa: Poetry is not to be understood; rather it’s to be resonated in reader’s mind. What is your view?

Boughn: I think we don’t understand what “understand” means. It means a lot of different things, which leads to confusion. If you are going to fix your hot water heater (which I just had to do), you need to understand the manual correctly. In that case, understanding involves narrowing meaning down to a clear series of instructions that if followed correctly will lead to a final goal—hot water. It’s a process of excluding erroneous interpretations. The notion that you can read a poem like a manual is destructive. To understand a poem is a different process because the language is mobilized — composed — toward a different end-which-is-not-an-end. Rather than this or that, the poem heaps on meaning — and and and — demanding that you open yourself to plentitude. To understand a poem is to give yourself to the poem’s particular knowledge, to be possessed by it – not to possess it.

Runa: Untraditional poetry or the poetry outside the heritage – what, in your view, will be the mark of new poetic language?

Boughn: The world is always remaking itself — the world is creation, creative — and the responsibility of the poet is to respond to that perpetual change with what the Roman poet, Ovid, called a carmen perpetuum, a perpetual song that breaks continually like the dawn on the new world. There’s no way to know what that song will sound like till you start singing it.

Runa: Is poetry a fully conscious construction? Construction and deconstruction – in your opinion, which one for the poet is the more ‘conscious’ important process?

Boughn: Nothing human is fully conscious, especially poetry. As Robert Duncan said, “the order man may contrive or impose upon things about him or upon his own language is trivial beside the divine order or natural order he may discover in them.” Emerson pointed out the we lie in the lap of an immense intelligence that continually nourishes us from beyond our meagre selves. To give yourself to the poem is to welcome that otherness, to give it a place to manifest itself from which it can teach us something we don’t know.

Runa: In terms of perception, how relevant is every incident of life or external indecisiveness in poetry?

Boughn: All of our knowledge, all of poetry’s knowledge, begins in the revelations of the specific emergence of the world, all of which has resonance in our being in the world. The “life”, the incidents that make up a day’s events, are only interesting in so far as they register or reveal incursions of that which is beyond us, that which emerging informs our lives. Your particular traumas and encounters are not really very interesting in and of themselves. It’s what they reveal or lead to. Dante’s thwarted love of Beatrice would be boring if it hadn’t led to the Commedia. We live at a moment when the flux of “history,” this being-in-time we are all caught up in, is in a turmoil of disintegrating social imaginary significations and determining concepts, “democracy” being a big one, and along with that, the idea of the inviolable value of the “individual” and his or her feelings. Time to move on.

Runa: In your view, is the poet responsible to society or him/her own self? What is the function of poetry in society?

Boughn: “Society” and “self” constitute a binary invented by the bourgeoisie to try and explain how its reality was different from feudal reality while energizing particular modes of being-together that were necessary to capitalism. They are imaginary states the poet may address, but the poet has only one responsibility, and that’s to the poem and its commitment to speak the truth, always. And to have fun with, to bring joy to, the work with language in all its manifestations. In so far as poetry tells the truth with joy, it’s working. The idea that there ought to be, or even can be, some mechanical cause and effect relationship between poetry and the resolution of social problems is based on the limited intelligence of sociology. The transformative gnosis of the poem goes on in multiple dimensions and is not measurable with statistics, sociology’s fundamental, underlying language.

Runa: When a poet’s poem triggers a reader and if s/he could assimilate the original poem in her/his own way of realization, can the reader construct her/his own poems from the original one? What is your opinion?

Boughn: Sure. That’s what we do. We are joyful thieves. We steal from other poets all the time. Hermes, as has often been pointed out, is the god of poets and thieves. You can’t even enter poetry without incurring a debt to someone. Poetry is an immense conversation that takes place in eternity between all the poets—that’s what Blake said—past, present, and future. We are privileged to be able to join and contribute to it. There is no other poetry.

About Author:

Michael Boughn, a third-generation Californian, born in Riverside, California in 1946, is a writer and teacher. He taught part-time at the University of Toronto for 22 years, covering courses in post-modern fiction, poetry, children’s literature, American literature, detective fiction and science fiction, among others. He left California in 1966 because of his opposition to the illegal and immoral war against Vietnam. Landing in Vancouver, Canada, he enrolled at Simon Fraser University, where he studied with Robin Blaser. Blaser introduced him to the work of William Blake, Ezra Pound, H.D., William Carlos Williams, Charles Olson, Jack Spicer, Robert Creeley, Ed Dorn and others. It was the defining moment of his life. From 1970 to 1979, Boughn worked in Toronto for a transport company, while organizing against the Vietnam war and supporting anti-racist activism in the south Asian community in Toronto. In 1982, he moved to Buffalo, N.Y. where he joined the graduate program at SUNY Buffalo. From 1983-1986 he worked as Robert Creeley’s graduate assistant and a cataloger in the Poetry/Rare Books Collection. His dissertation was a descriptive bibliography of H.D., published in 1993 by the University of Virginia. Graduating with a PhD. in 1986, he remained in Buffalo, working with another of his teachers, the poet and Blake scholar John Clarke, to produce the magazine, “intent: a newsletter of talk, thinking and document.” He also started a micro press, shuffaloff, which over the years has irregularly published work by Robert Creeley, John Clarke, Robin Blaser, and a number of younger poets including Elizabeth Willis, Jorge Guitart, and Lisa Jarnot. Recently, shuffaloff joined forces with Victor Coleman’s Eternal Network to publish a number of “Joints” featuring chapbooks by venerable writers Robert Duncan and Ed Dorn, as well as new work by young Toronto writers such as Emily Izsak, Oliver Cusimano, and Michael Harman. In 1991, Boughn married Elizabeth Brown, and the following year returned to Canada. He swore allegiance to the Queen and her heirs in September, 2001, and became a Canadian citizen. His publications include Iterations of the Diagonal (1995), A little post-apocalyptic suite for RC with thanks for the rhino (1996), One’s own MIND (1999), Dislocations in Crystal (2003), and 22 Skidoo/SubTractions–Opus minus one (2009). Cosmographia — a post-Lucretian faux micro-epic, was short-listed for Canada’s Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 2011. His most recent work is Hermetic Divagations—After H.D. With Victor Coleman he edited Robert Duncan’s The H.D. Book. He currently edits the online poetry news magazine, Dispatches from the Poetry Wars (https://www.dispatchespoetrywars.com) with Kent Johnson.

Michael Boughn, a third-generation Californian, born in Riverside, California in 1946, is a writer and teacher. He taught part-time at the University of Toronto for 22 years, covering courses in post-modern fiction, poetry, children’s literature, American literature, detective fiction and science fiction, among others. He left California in 1966 because of his opposition to the illegal and immoral war against Vietnam. Landing in Vancouver, Canada, he enrolled at Simon Fraser University, where he studied with Robin Blaser. Blaser introduced him to the work of William Blake, Ezra Pound, H.D., William Carlos Williams, Charles Olson, Jack Spicer, Robert Creeley, Ed Dorn and others. It was the defining moment of his life. From 1970 to 1979, Boughn worked in Toronto for a transport company, while organizing against the Vietnam war and supporting anti-racist activism in the south Asian community in Toronto. In 1982, he moved to Buffalo, N.Y. where he joined the graduate program at SUNY Buffalo. From 1983-1986 he worked as Robert Creeley’s graduate assistant and a cataloger in the Poetry/Rare Books Collection. His dissertation was a descriptive bibliography of H.D., published in 1993 by the University of Virginia. Graduating with a PhD. in 1986, he remained in Buffalo, working with another of his teachers, the poet and Blake scholar John Clarke, to produce the magazine, “intent: a newsletter of talk, thinking and document.” He also started a micro press, shuffaloff, which over the years has irregularly published work by Robert Creeley, John Clarke, Robin Blaser, and a number of younger poets including Elizabeth Willis, Jorge Guitart, and Lisa Jarnot. Recently, shuffaloff joined forces with Victor Coleman’s Eternal Network to publish a number of “Joints” featuring chapbooks by venerable writers Robert Duncan and Ed Dorn, as well as new work by young Toronto writers such as Emily Izsak, Oliver Cusimano, and Michael Harman. In 1991, Boughn married Elizabeth Brown, and the following year returned to Canada. He swore allegiance to the Queen and her heirs in September, 2001, and became a Canadian citizen. His publications include Iterations of the Diagonal (1995), A little post-apocalyptic suite for RC with thanks for the rhino (1996), One’s own MIND (1999), Dislocations in Crystal (2003), and 22 Skidoo/SubTractions–Opus minus one (2009). Cosmographia — a post-Lucretian faux micro-epic, was short-listed for Canada’s Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 2011. His most recent work is Hermetic Divagations—After H.D. With Victor Coleman he edited Robert Duncan’s The H.D. Book. He currently edits the online poetry news magazine, Dispatches from the Poetry Wars (https://www.dispatchespoetrywars.com) with Kent Johnson.

Runa Bandyopadhyay

Though Runa Bandyopadhyay is a Scientist in profession yet fully addicted by the drug of innovative experimental literature. She is a bilingual poet, translator, essayist and critique from Kolkata, India. Her latest book Nocturnal Whistle (2019), an unconventional process of reviewing a book to breakdown the conventional literary criticism and recreates her own poems in the process. Its Bengali Collection Antarbarty Pangkti (Between the Lines, 2012) and Tamaser Alokbhromon (Light-Travel of Dark, 2017) was published by Kaurab. In 2019, she translated and co-edited Bridgeable Lines: An Anthology of Borderless World Poetry in Bengali with 12 contemporary American poets. She has translated numerous international poets bidirectional between English and Bengali including Charles Bernstein, Murat Nemet-Nejat, Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge, Barin Ghosal, Swadesh Sen, Alok Sarkar etc. She also authored 4 poetry books, 2 story books, 1 hybrid essay in Bengali.

Though Runa Bandyopadhyay is a Scientist in profession yet fully addicted by the drug of innovative experimental literature. She is a bilingual poet, translator, essayist and critique from Kolkata, India. Her latest book Nocturnal Whistle (2019), an unconventional process of reviewing a book to breakdown the conventional literary criticism and recreates her own poems in the process. Its Bengali Collection Antarbarty Pangkti (Between the Lines, 2012) and Tamaser Alokbhromon (Light-Travel of Dark, 2017) was published by Kaurab. In 2019, she translated and co-edited Bridgeable Lines: An Anthology of Borderless World Poetry in Bengali with 12 contemporary American poets. She has translated numerous international poets bidirectional between English and Bengali including Charles Bernstein, Murat Nemet-Nejat, Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge, Barin Ghosal, Swadesh Sen, Alok Sarkar etc. She also authored 4 poetry books, 2 story books, 1 hybrid essay in Bengali.